“When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. All the nations will be gathered before him” (Matthew 25:31-32)

Here we find ourselves at the end of another Christian year – at the feast of Christ the King – and our Gospel reading presents us with what I believe is the most glorious vision of Christ as king that we see in the Gospels.

Jesus gives us this image Himself, and it’s an image of a coronation celebration. The new age is finally being inaugurated and the long-awaited king is finally being crowned, and all the king’s subjects are gathered before the throne, presumably so that they can express their loyalty to their new sovereign as he begins his reign.

This sort of scene would not have been unfamiliar to the people Jesus was initially addressing. Even if they had not been present at the coronation of Augustus Caesar or any of his successors, they certainly would have read or heard about such events, and would have been able to easily imagine the glorious nature of such a ceremony.

That original audience would also have understood that such coronations included not only the opportunity for the faithful to express their allegiance to their new monarch, but also the public banishing or punishment of the new king’s enemies. In the depiction Jesus gives, it is the king himself who discriminates between who are his loyal servants and who are his enemies, and he does so in a most surprising way.

According to Jesus, the new king assesses the loyalty of His people to Him – the King of the kingdom – by judging how well they have been looking after those who are at the extreme opposite end of the social spectrum!

“I was hungry, and you gave me food, I was thirsty, and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked, and you gave me clothing, I was sick, and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’ … ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did it to me.’” (Matthew 25:35-36, 40)

This is one of those Bible passages that is not hard to understand, as much as it is hard to understand what we are supposed to do with it, as most of us balk at the idea that our lives might be judged solely on the basis of how well we looked after the poor and the dispossessed. Indeed, I can understand why even those who pride themselves on taking the Bible literally are hesitant to take this passage too literally.

It’s a bit perplexing from a theological point of view. At the same time though, it is straightforward from a practical point of view. The very clear mandate coming out of this passage is that we should be spending a lot more time looking after the poor and the needy, and visiting those who are sick and imprisoned. And given that all of us who are a part of the Holy Trinity community have this week (either directly or indirectly) been involved in visiting those in prison, I thought I’d spend the rest of my time today debriefing that experience with you.

I arrived on Manus Island last Thursday. How I got there is itself a bit of a story, and it begins with Ruth. Or perhaps it began before that, when I started raising questions about what was happening on Manus Island and what the church was doing.

It seemed to me that there was no real media coverage of what was going on, but that people were clearly suffering. and I was keen to know what the body of Christ was doing about that.

As a member of the church in Australia, I was very concerned, as it seemed that my country was causing this suffering, and I wondered what we Christians in Australia were doing to hold our government to account. I also wondered what our Christian brothers and sisters in Papua New Guinea were doing about all this, as I figured that they would be equally concerned about it.

So, I started making enquiries – calling our bishop, calling the Anglican Board of Mission (who I knew had connections in PNG) and talking to other local church leaders, as well as raising questions online through my various social networks. It was when I posted an appeal on ‘Flocknote’ though (our church notice-board) that Ruth took hold of the idea and connected me with ‘Getup!’, which led to a series of meetings, that led to my boarding a plane for Papua New Guinea a few days later.

We arrived on Manus Island, which is a small island to the north of the mainland of Papua New Guinea (about 7 km deep and 30 km wide) on the Thursday morning, and we had the privilege of enjoying the hospitality of local residents who were also concerned about the plight of the men in the Immigration Processing Centre.

For any who don’t know the full story, the Australian government had been trying to close their facility, located near the town of Lorengau, that had housed around 600 men for the last four and a half years, ostensibly to move the men to other newly constructed facilities, also located on Manus Island. Most of the men though had refused to move, and the authorities had clearly been reluctant to move them forcibly, leading to a stand-off. When we arrived, the men had been holding out for nearly a month, pooling food supplies and constructing wells in an attempt to get fresh water.

I had heard lots of questions raised as to why these men refused to move when (according to Australian authorities) they had wonderful new facilities waiting for them. When I first arrived on Manus Island, I too had no idea as to why these men were holding out and trying to live on in a decommissioned dysfunctional facility. When I got to meet the men in that facility, it all became crystal clear.

That visit took place on the Friday night, after we were able to secure a small motor-boat, and were able to make our way around the island by water to the beach where the detention facility was located, being careful not to land at the naval base, which was located next door and shared the same beach.

This was not as easy as it might sound, as the whole trip was made in the pitch dark, with the inmates of the detention communicating with us via text messages, and trying to subtly indicate their presence on the beach by use of flashlight.

It was further complicated by repeated text exhortations of “for God sake, turn off your engine. We can hear you!”, which meant that we had to try to drift in over the last kilometre or so, using the tide. Even so, somehow, after some hours on the water, we were able to successfully rendezvous with the men, and it was certainly worth the effort.

There was no functional lighting in the decommissioned facility, but the men had become very adept at using the lights on their mobile phones to get around, and they managed to give us a comprehensive tour of their environment over the hours I was with them. They showed us the wells they had constructed to keep fresh water flowing, and explained also how local police had come in and smashed those wells and poured rubbish into them, in an attempt to force the inmates to leave.

The descriptions they gave of regular harassment by the police was distressing, and yet their commitment to non-violence was extraordinarily impressive. They were physically pushed around and verbally abused, but they refused to respond in kind. When we asked them how they developed their commitment to non-violence, they said that after four and a half years, they had learnt what worked and what didn’t.

I listened to the men as they shared their stories. Many of them had escaped from warzones in places like Afghanistan or Somalia or Sri Lanka. Others were facing more subtle forms of persecution, such as the young Iranian boy who had apparently converted to Christianity and had been labelled an apostate by his peers.

Their stories were, in every case, reminders that we were not dealing with criminals. On the contrary, we were with men who had escaped intolerable environments, only to be intercepted by Australian authorities and imprisoned in another intolerable environment, for a period of detention that might never end!

A number of these men said they did not want to go to Australia – certainly not now. Many felt understandably bitter about the way they had been treated. One man in his twenties said “I have lost my youth in this place. I just want my life back.”

I spent time with one man there who had fled Afghanistan four and a half years ago. He is a part of a persecuted minority group in Afghanistan and he left his pregnant wife with her family to seek a safe environment for them in another land. Now, four and a half years later, he shows me pictures of his young son on his mobile phone – a boy he has never met, and he wonders when he will get to meet him.

Again, these men are not criminals. Most of them have been interviewed by the authorities and judged to be genuine refugees. They just wait and wait and wait, week after week, and month after month, and year after year, in this ‘processing centre’ that never seems to process anybody.

As we spoke with the men, and as we spoke with their leaders – Aziz and Behrouz – what became very clear to me was that these men had developed a really functional community between them!

They had a solid leadership structure with strong democratic accountability, demonstrated through regular camp-wide meetings. They had a centralized health-care system, with medications pooled and distributed to those who needed the most, and with people rostered on to take care of the mentally ill – walking them around the facilities and talking to them, so as to ensure they didn’t harm themselves. Those with expertise in engineering were in charge of the construction of the wells and the maintenance of the facilities.

In short, the men of the Manus Island Refugee Processing Centre had learnt to work together, to depend on each other and to sustain one another. It was a highly functional community, and when I realised that I understood why they didn’t want to be moved and broken up into various new detention centres. Why would these men abandon each other – their brothers who they knew they could trust – for promises offered them by the Australian government, whom they knew they could not trust?

Interestingly, before arriving on Manus Island, I had just finished reading a book called “Tribe” (by Sebastian Junger), which looks at the way so-called ‘primitive’ tribes function, where people live in close-knit communities, in mutual dependence on one another, in contrast to the way larger cities and nation-states function.

The key thesis of the book was with regards to those returning from war, suffering post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The author of “Tribe” suggests that the problem for these men is not the war environment they’ve come from, but the difficulty of adjusting from a living environment where people live closely together and depend on each other for their survival, back into an impersonal community where everyone seems to be only interested in themselves!

What I found in that detention centre on Manus Island was a really well functioning tribe, with men living in real community, depending on one another for their survival, and caring for each other in a very powerful way!

For me, the highly functional nature of that community was best illustrated by what happened after I left them.

For those who didn’t hear, the extraction operation did not go smoothly. As we were making our way back to the boat on the beach, lights started flashing, apparently courtesy of personnel from the naval base. The result was that I got away in the boat, while my companions – Jarrod and Olivia – ended up back into the detention centre, where they spent another day before we successfully extracted them.

What impressed me over that 24-hour period was that Olivia, who is an attractive young girl, trapped inside a detention centre with four hundred sex-starved men, never felt herself to be at risk. The men said to her, “you are our sister. We will take good care of you”, and they did.

If I had more time, I would share with you something of the adventure of my own extraction. ‘Adventure’ is probably the wrong word as it suggests that it was fun. The short version of the adventure was that it involved spinning around in a boat amidst coral reefs in the pitch black (except when the searchlight from the naval base caught us) with the crew of three inexplicably spending most of their time in the water at the back of the boat, speaking excitedly in Pigeon (which I don’t understand a word of).

I later discovered that, in the mayhem, the boat’s propeller had been damaged by one of the coral reefs and the drive pin (whatever that is) needed to be replaced. My crew had been trying to fix the engine under water without using any light that would give away our location. I was later told that the repair was a miracle of God’s grace.

Those who know me well know that I don’t fear a lot of things, but that I do actually have a bit of a phobia when it comes to small boats, ever since my darling daughter, Veronica, came very close to being drowned in a boat (of very similar size to the one I was in that night) when she was little. Suffice it to say that it was a long night for me.

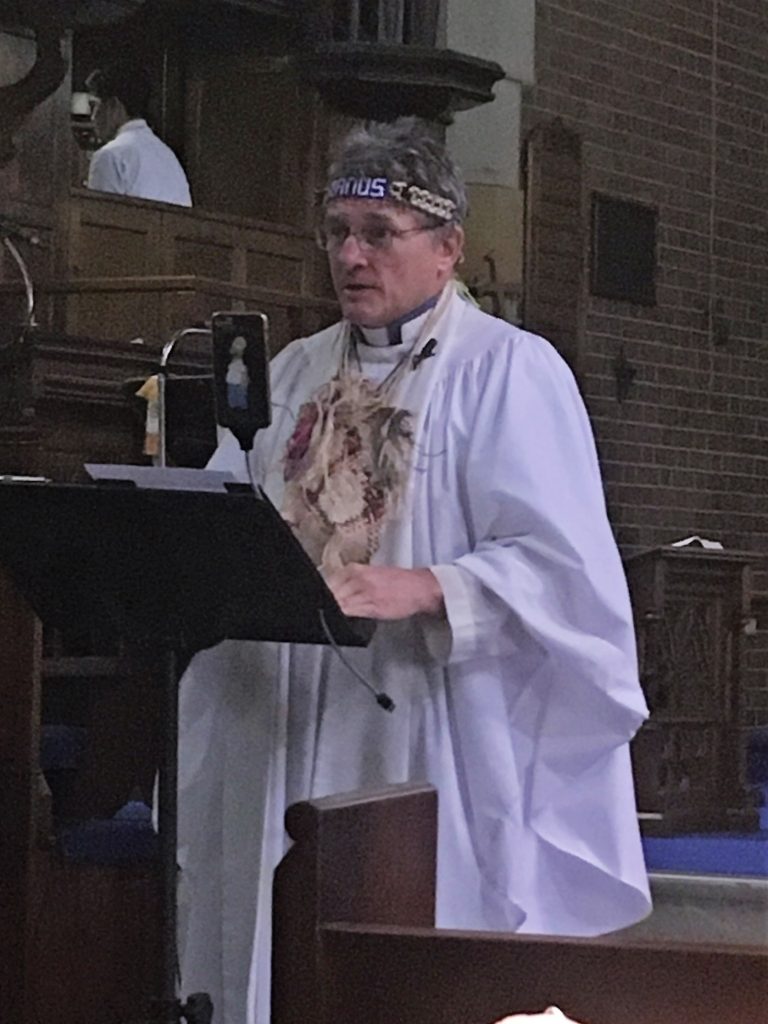

Thanks be to God, at any rate, I made it back safely to shore that night (or morning, as dawn was breaking by the time we returned). I didn’t sleep well, but I did have the privilege, later that same day, of meeting with the members of the Manus Island boxing team, who were about to head off for competition on the mainland. Indeed, I was even able to do a couple of rounds with the Manus Island champion, and they presented me afterwards with an official Manus Island headband, along with a hand-woven man-bag, designed to be worn around the neck.

As you can see (from the photo below), I look like an absolute twit. The men of Manus were far more complimentary though, telling me “you look good”. I asked the sister of the man we were staying with “do you think the girls of Manus might go for me in this outfit?” and she said “maybe”. I have a feeling those Manusians were just being nice to me, but the truth is that the native people of Manus Island truly are nice people – warm and hospitable and generous and caring!

Yes, it is true that some of the inmates at the detention centre had experienced violence at the hands of local ruffians (such as can be found in every community) and yet it was also true that there was a concerted effort going on between concerned people across the island, and most especially between the churches, to get food and medical aid to these people, and to get the word out about their predicament.

“I was hungry, and you gave me food, I was thirsty, and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked, and you gave me clothing, I was sick, and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’” (Matthew 25:35-36)

May God have mercy on these good men – the men of the Manus Island Refugee Processing Centre – and on all the good people of Manus Island. May God have mercy on us all!

first preached at Holy Trinity on November 26th, 2017