Happy Easter … again.

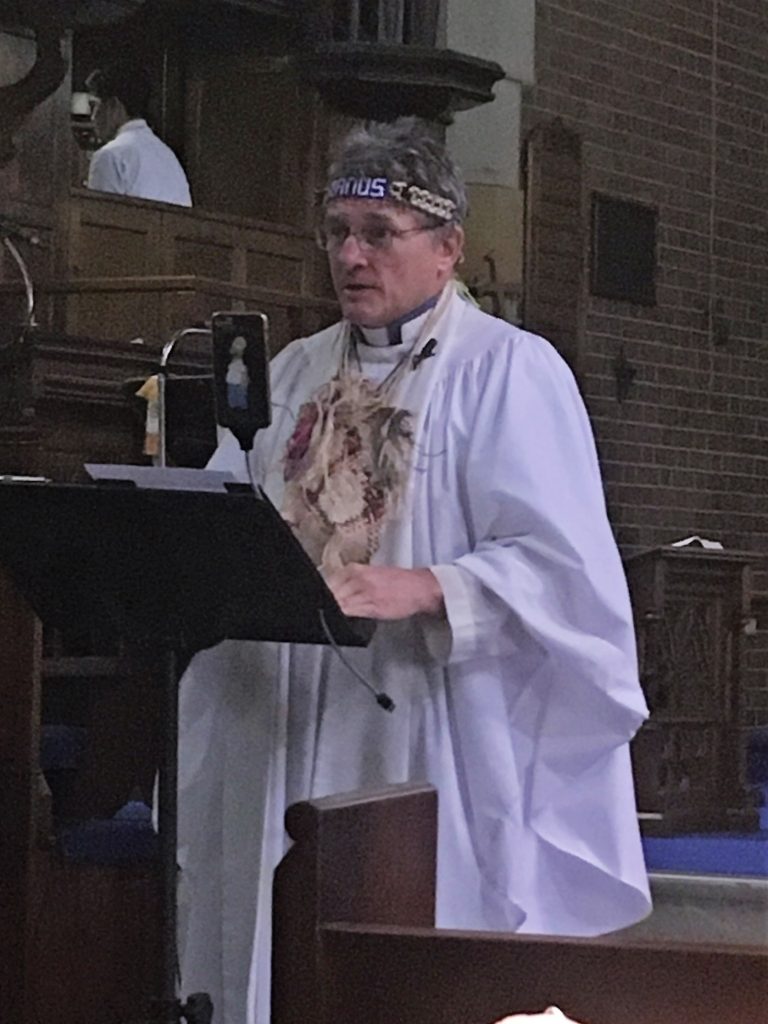

When I say ‘again’, I’m not simply alluding to the fact that I’ve already given you Easter greetings today, but I mean ‘again, this year’, as this is now my 28th Easter as parish priest of the church of the Holy Trinity in Dulwich Hill!

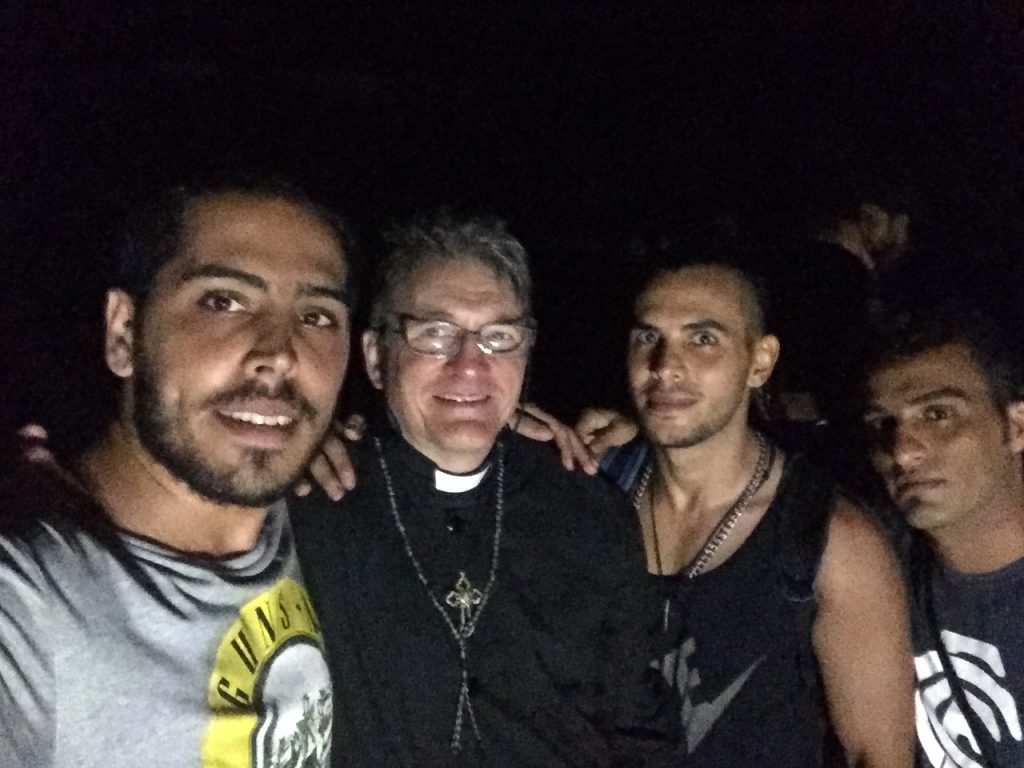

Who would have guessed that the romance would last this long? Who would have guessed we would spend so many Easters together, though, to be exact, I’ve only been present for 27 of our 28 Easter Sundays over those years. On the other one (2014) I spent the morning in Westminster Abbey and much of the evening in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London in the company of our dear brother, Julian Assange.

I’ve been thinking a lot about dear Julian lately, as it seems unlikely that he’ll spend another Easter in the Ecuadorian Embassy (for better or worse). How good it would be if he could share next year’s Easter Sunday service with us here, though the possibility of that happening has never looked more remote than it does right now.

At any rate, there are many wonderful benefits that come with sharing so many special days like Easter with people you love, though the regularity of it all does also present special challenges to the preacher. How do I come up with something fresh this year – something that you haven’t heard twenty-six times already!

Of course, not everybody here today has been here to hear each of those twenty-six previous Easter Day sermons, but the evolution of our community does, in itself, bring its own challenges, for you guys are frankly a far more demanding audience than the happy flock I addressed here twenty-seven years ago!

I appreciate that I had the advantage back then of being the first cleric to accept an appointment in this place for what must have seemed like an eternity to the righteous remnant who were still hanging on here – feeling as if they’d been forgotten by the Diocese and left to atrophy and die. Dulwich Hill was just too rough a neighbourhood for any self-respecting family to move into the area. The fact that I was willing to be here, to share the Dulwich Hill experience with the band of brothers (and sisters) who were still holding out meant that I didn’t need to do much to feel appreciated. Indeed, so long as I was speaking English, it probably wouldn’t have mattered much what I had said. The good people of Dulwich Hill were just glad to have someone who was willing to get in the pulpit!

Moreover, we were a much more homogenous unit back then than we are now. We weren’t entirely white and middle class by any means, but there weren’t a lot of us then, and even fewer of us under the age of seventy. All being at a similar stage of life meant that we were almost all facing very similar life challenges, and that made it a lot easier to work out where the Scriptures really spoke to the community.

We are a far more diverse group today. We span a wide age-range, from those who can’t yet walk to those who are struggling to still walk. We come from various ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and some of us hold down high-paying professional jobs while others amongst us are struggling to find a job. Moreover, I believe that we have never been a more spiritually diverse community.

I take some pride in us being a spiritually diverse community, and by that I mean that were are not all the same kinds of Christians.

Perhaps some of us wouldn’t even call ourselves Christians (and that’s OK too) though I’m pretty sure that most of us would be happy to accept that label. Even so, I’m equally sure that there is a vast diversity amongst us when it comes to what it means for each of us to be followers of Jesus.

Of course, at one level, everybody’s spiritual experience is different, and so no two religious people of any variety are going to identical in their beliefs and self-understandings. Even so, there are a broad spectrum of distinct but nonetheless well-defined colours within the Christian spiritual rainbow (so to speak), and I think we see many of those different hues and colours represented amongst us here.

When I was a young believer, people would often ask me ‘what kind of Christian are you?’, and they’d be looking for a label like ‘Catholic’ or ‘Protestant’ or ‘Evangelical’ or some combination of the above, such as ‘liberal evangelical protestant’.

These labels can be helpful in defining what kind of Christian you are, but they function primarily to assign you to a particular tribe within the Christian family, rather than to say anything specific about what Jesus means to you. A more helpful way of appreciating Christian diversity, I think, is to look at what religious beliefs (or ‘dogma’s) are most central to your spiritual understanding.

When you think of yourself as a Christian (if you do think of yourself as a Christian) what exactly does this mean to you? Does it mean being part of a broad spiritual family who have a mission to accomplish in the world? Does it mean that your sins are forgiven? Does it mean that you’re going to Heaven when you die? Does it mean that you experience a personal relationship with Jesus?

Of course, you may want to say that it means all of those things to you and more. Even so, which is most central to your self-understanding? This is by no means a trivial question, as I remember being warned at seminary of those who would shift the deeper theological truths away from centre of our spiritual self-understanding.

I went to Moore College – a conservative Evangelical seminary. What theological truth do you think is at the core of their spiritual self-understanding? The atonement – the truth that God in Christ is reconciling the world to Himself through the cross. I remember there being warned specifically about those who put at the centre of their Christian thinking, not the atonement but the incarnation – the fact that in Christ God became human and shared our human experience with us.

That might not sound like much of a shift in emphasis. Indeed, it might not sound like a shift at all, as surely it’s possible to hold to a belief in both the atonement and the incarnation without the two being in conflict, and indeed it is, but don’t underestimate how such a shift in emphasis can transform you into a very different kind of Christian.

Without wanting to over-simplify the situation, let me suggest to you that those who’s spirituality centres on the atonement tend to be more Heavenly-minded, often seeing the whole point of Christianity as being a means to get you into Heaven when you die. That isn’t always the case, of course, but a focus on the atonement and forgiveness of sins tends to move us in that direction.

A focus on the incarnation, on the other hand, tends to be a more this-worldly focus. God shares our humanity in Christ, and if the human condition is good enough for God then humanity is something that is worthy of respect. God did not give up on humanity, so neither should we. As He came down and shared our condition, so we too must empty ourselves and share in the struggles of all our sisters and brothers.

Those who know me well and have been listening to my sermons for any length of time probably realise that for me, it’s neither the atonement nor the incarnation that are at the centre of my spiritual thinking. It’s Jesus’ teachings on the Kingdom of God

That was a shift in focus I made many years ago after reading the so-called ‘liberation theologians’ who saw in Jesus’ teaching about the coming Kingdom of God a hope for a whole new social order – a world where poor people were fed and where there is no more injustice or war or oppression of the weak.

What I’m talking about here are different spiritual orientations, each of which have Jesus as their focus, but which emphasise different aspects of His life or teaching. These three different areas of focus that I’ve mentioned are by no means exhaustive of what we find amongst those who call themselves Christians in different parts of our world. Indeed, one of the great discoveries for me in the last few years has come from interacting with more sisters and brothers in the Christian Orthodox tradition.

I was fascinated to find that in the Orthodox tradition – be it Greek Orthodox or Syrian Orthodox or in other branches of Christian Orthodoxy – the focus tends to be not on the atonement nor the incarnation nor on the Kingdom of God. The Orthodox tradition focuses on the Transfiguration – on seeing Christ in His glory, and in the hope we have of ourselves one day seeing Christ in all His transfigured beauty!

What kind of Christian are you? What is the focus of your spiritual understanding? When you think of Jesus, what do you see? Do you see someone with a bleeding heart, as depicted in so much Catholic art? Do you see a young man who is very good-looking with blond hair and blue eyes and who speaks with a sophisticated American accent? Do you see someone else entirely?

When you think of the teachings of Jesus, what teachings first come to mind? Do you think of John 3:16 – ‘for God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten son’? Do you think of the beatitudes – “blessed are the peacemakers … blessed are those who hunger and thirst for justice” (Matthew 5).

When you think of the life of Jesus, what do you see Him doing? Do you see Him touching a leper? Do you see Him giving dignity to women? Do you see Him healing the sick? Do you see him suffering on the cross?

There are many kinds of Christians, and the truth is that all of them are connected in some way to the Gospels and to the wisdom that has been passed on to us through our forefathers and foremothers in the faith. I’m not suggesting that all forms of Christian spirituality are therefore equally well connected to the Scriptures or to the wisdom that has been passed down, but the key thing that I do want to say today is that all forms of the Christian faith in their multi-faceted variety all have their starting point here – on Easter Sunday – in the resurrection of Jesus from the dead!

Wherever it ends up, Christian faith begins here – on Easter Sunday morning.

Whatever happened on Good Friday – however central that was to the life of Jesus and to the history of human-kind – no one would have bothered to interpret what had happened on the cross had it not been for the fact that Jesus’ tomb was empty three days later.

However wonderful the teachings of Jesus – however much He pointed us to a new reality and urged us to build a different kind of world – nobody would have bothered remembering those teachings were it not for the fact that Jesus, having died on Friday, was somehow found to be alive again on Sunday!

What I love most about the resurrection stories that we read in the Gospels is that they are all so incomplete and unsatisfying. We like stories that have solid conclusions just as we like stories that have happy endings, and we just don’t get any of that in the New Testament Gospels!

We heard the resurrection account from John’s Gospel this morning, which is generally assumed to be the last of the four accounts of the life of Jesus written. Indeed, there may have been fifty years between the publication of the first Gospel and the publication of this last Gospel. Even so, despite the fact that the early church had all that time to put together a properly connected story, it still comes across as being radically incomplete!

It’s the story of the resurrection, but there is no actual account of the resurrection – no description of the miraculous body of Jesus somehow coming back to life. Far from it, instead of any depiction of the spectacular and miraculous, we get a story of people running around and looking for Jesus, and of a person whom Mary initially took to be a gardener, but then later became convinced was Jesus!

If you find that unsatisfying, go back to Mark (presumably the first Gospel written) where nobody seems to even see Jesus initially, but where the account ends with the women scared and not knowing what to do while the men are all in hiding!

Christian faith begins with this sense of confusion at not knowing what to do with the empty tomb! Gradually Jesus’ followers start to work it out, and they go back and reinterpret things Jesus said and did in the light of His resurrection, but as we leave those early followers in their befuddlement, the story is anything but finished.

Christian faith starts at the empty tomb but the story doesn’t end there. The Gospel narratives seem to be deliberately open-ended. They don’t have a straightford happy ending. Where does the story end? It ends here – in all the diversity of interpretation and in all the various forms of Christian expression that we see around us today.

We are the conclusion of this story. I’m not saying that we are necessarily the final chapter of the story, as it’s a story that is still being written. What I am saying though is that we are the current end-point of the process of confused interpretation that has gone on for the last two thousand years – a process of trying to come to terms with what happened on that Easter Sunday morning when Jesus’ tomb was found empty.

He is risen! He is risen indeed! Yes! That’s where our story of faith begins. It’s up to us now to help shape how our great story is going to end.

First preached at Holy Trinity, Dulwich Hill, on Easter Sunday, 2018.

The following press release is courtesy of

The following press release is courtesy of